This is Part 4 of a series that analyzes the rhetoric of Trump’s announcement speech on June 15, 2015. It’s all there. Everything that followed in three presidential elections. Everything that has consumed us for almost a decade.

The Death of Policy, The Erasure of History

As I wrote earlier in this series, Trump’s Gilded Escalator speech is more traditional than we might remember. He presents himself as being the new Reagan, and the speech is more scripted. Trump also follows the traditional structure of an announcement speech. The pattern can roughly be broken down into three parts.

In the first third, candidates introduce themselves, align themselves with traditional American values, and describe the current state of the nation. The purpose of this section is to explain why they are running. In the middle third, candidates begin with the actual announcement. They say, basically, “This is why I am running for President of the United States of America.” They say more about their qualifications. They introduce their family. The purpose of this part of the speech is to establish the candidate as the right person who can solve the problems outlined in the first third. The last third of the speech is typically devoted to policy—their plan to set the nation on the right path.

In this analysis of Trump’s Gilded Escalator speech, we are at the beginning of the middle part. Trump introduces his family, he tells his own American Dream story about “starting off in a small office” and going into Manhattan, over his father’s objections. This is the most mythic part of Trump’s speech. He is the strong man who can stand up to the powerful father figure (see my “Divided America: An Origin Story,” posted August 18). As I wrote in “Divided America: An Origin Story” (posted August 18), a particular family structure with a domineering father is central to the evolution of the MAGA movement. A figure who stands up to the domineering father is a hero.

As Trump transitioned in the last third of the speech, the policy section, he pulled out notes and reads his goals as president: he will repeal Obamacare (he did not, and, in the VP debate, Vance claimed that Trump saved it); build a wall and make Mexico pay for it (he built a small section of it, but Mexico did not pay for it); be tougher on ISIS (maybe); find his own George Patton (most of the generals who served in his administration now say he is unfit for office); support the Second Amendment (yes); eliminate Common Core (nope); rebuild infrastructure (he did not pass an infrastructure bill, but Biden did); save Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security (they are still there, so okay); renegotiate trade deals (he did this); strengthen the military and take care of veterans (he refused to visit a WWI cemetery in France because it was raining and he didn’t want to mess his hair); and bring back the American Dream (he passed a tax cut for the upper 3 percent, so the American Dream is still a little distant for most of us).

It is a long list, which is clearly scripted, which means written for but probably not by Trump. When he is able to follow the script, Trump seems a bit more like a traditional politician. Even Hillary Clinton would likely have agreed with most of this laundry list of goals. This, too, is a nod Reagan. When Reagan accepted the Republican nomination in 1980, he stunned the crowd by praising FDR. In scripted moments, Trump will continue to be more of a centrist. When he accepted the Republican nominate at the 2016 RNC, he even mentioned LBTQ rights, although he recited the letters slowly, as if he were searching his memory. Ivanka mentioned providing daycare as a goal.

By the time Trump is running for reelection in 2020, the Republican Party will not have a platform—that is, an agreed upon set of policies. Why? Policies are another form of restrain on strongman politicians.

In 2016, however, Trump was trying to be like Reagan. He was trying to be normal. Yet, for all of the normality of Trump’s Gilded Escalator speech, it was viewed as a break with tradition—as it should be.

I have saved discussion of a key section of Trump’s speech until now because it will be at the center of Trump’s 2016 campaign and all that follows. And it demonstrates how much he will shift the norms of political rhetoric. It is the section that drew the most attention, both from his supporters and critics.

This is, of course, his comments on immigration, which appear to have been delivered extemporaneously: “When do we beat Mexico at the border? They’re laughing at us, at our stupidity. And now they are beating us economically. They are not our friend, believe me. But they’re killing us economically. The U.S. has become a dumping ground for everybody else’s problems.” After a pause for cheers, Trump continued: “Thank you. It’s true, and these are not the best and the finest. When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re not sending you. They’re not sending you. They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”

These comments violated the norms of political correctness (don’t stereotype ethnic groups), the norms of political strategy (don’t alienate entire cohorts of voters, that is, Hispanic citizens), and the norms of patriotism (never imply that America is not the greatest country in the world). We will become used to Trump making this kind of comment and then following it with an insincere qualification: “Some, I assume, are good people.”

The qualification at the end is a crucial strategy. Trump will continue to make outrageous comments (like, “I will be a dictator); then, he pull it back a notch or two by adding a qualification (“but just for a day”) or by saying he was just joking (typically, a few days later). Hardcore MAGAs hear and applaud the outrageous comment. Supporters of Trump who are more centrist hear the qualification and think to themselves, “He’s not so bad.” Or, “He didn’t really mean that he will actually be a dictator.” This structure allows Trump to play to multiple audiences at once, and it allows the audience to find their own level of comfort—their own way of supporting him.

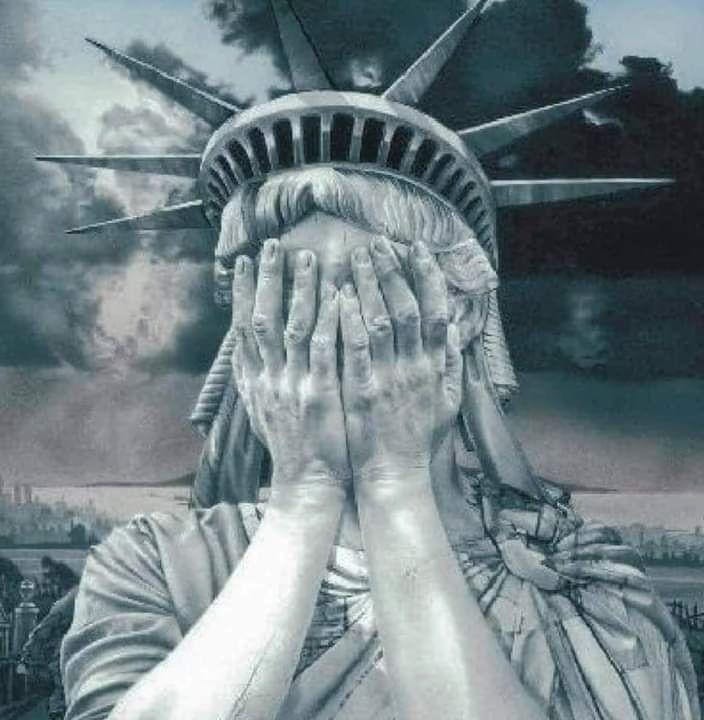

Trump’s view of immigration is simple and devoid of history. He is incapable of acknowledging the positive contributions of immigrants to our country, and I am sure the sentiment behind the plaque on the Statue of Liberty (“give us your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free”) never resonated in his heart. Our country has never had an open border, as Trump claims. Americans as a whole have always had a complicated view of immigration. The Naturalization Act was passed in 1790. Immigrants were typically viewed as diseased or subhuman. When Trump speaks of immigrants, there is no history. There is no compassion.

As I have pointed out repeatedly, Trump erases history. He speaks about making America great again, returning to some earlier time, before we had problems like mass immigration. He speaks of a dystopian future. He almost never speaks of actual history. When he does, his facts are off.

As I have also pointed out, Trump has not only broken many of the norms of our political system; he has also managed to make his actions seem normal, largely through the sheer volume of his breeches. See my “Democratic Thinking: The Death of Normality,” posted September 2.

This is why, in this moment, history is so important. It brings us back to the values on which our country was founded and the values that have evolved over the last 240 years. It also brings us back to traditions—to normality.

We can, for example, ask: When in the history of our country has a presidential candidate said he wanted to be a dictator? To those who defend Trump by saying he was just joking, we can ask: When in the history of our country has a presidential candidate even joked about wanting to be a dictator or president for life?

If the answer to the history question test is “never,” we should be concerned about the future of our democracy.